Golden Mountain: Putting David Hume's Empiricism to the Test with the Midjourney AI Text-to-Image Generator (and Vice Versa!)

Take a moment and imagine a golden mountain. Is it just the synthesis of the properties of gold somehow morphed into the shape of a mountain?

British empiricist philosopher David Hume famously held that all of our ideas and concepts, except for mere relations of ideas like mathematics, arise from the synthesis of items from our previous experience:

But though our thought seems to possess this unbounded liberty, we shall find, upon a nearer examination, that it is really confined within very narrow limits, and that all this creative power of the mind amounts to no more than the faculty of compounding, transposing, augmenting, or diminishing the materials afforded to us by the senses and experience. When we think of a golden mountain, we only conjoin two consistent ideas, gold, and mountain, with which we were formerly acquainted. A virtuous horse we can conceive; because, from our own feeling, we ca conceive virtue; and this we may unite to the figure and shape of a horse, which is an animal familiar to us. … The idea of God, as meaning an infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being, arises from reflecting on the operations of our own mind, and augmenting, without limit, those qualities of goodness ad wisdom. We may prosecute this enquiry to what length we please; where we shall always find, that every idea which we examine is copied from a similar impression. (David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Section II: Of the Origin of Ideas)

Given the recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI) image generation, I thought it would be interesting to put some of David Hume’s examples to the test, to see what results from attempting to synthesize items such as golden mountain, virtuous horse—and, although more abstract, infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being.

I’ve recently been experimenting with Midjourney, a text-to-image generator tool that produces a mind-boggling array of possible visible imagery by means of various forms of synthesis and diffusion. While many Midjourney query results are exactly as one might expect them to be, often the results are delightfully innovative and novel, even humorous for their unexpected juxtapositions—juxtaposition of the unexpected being an essential element of humor.

So let’s proceed with putting David Hume’s empiricism and his account of the origin of ideas to the test with Midjourney—and, perhaps, vice versa as well, since the ability to capture highly abstract ideas and concepts is arguably a good benchmark for the level of sophistication of artificially intelligent systems in general, and Midjourney in particular.

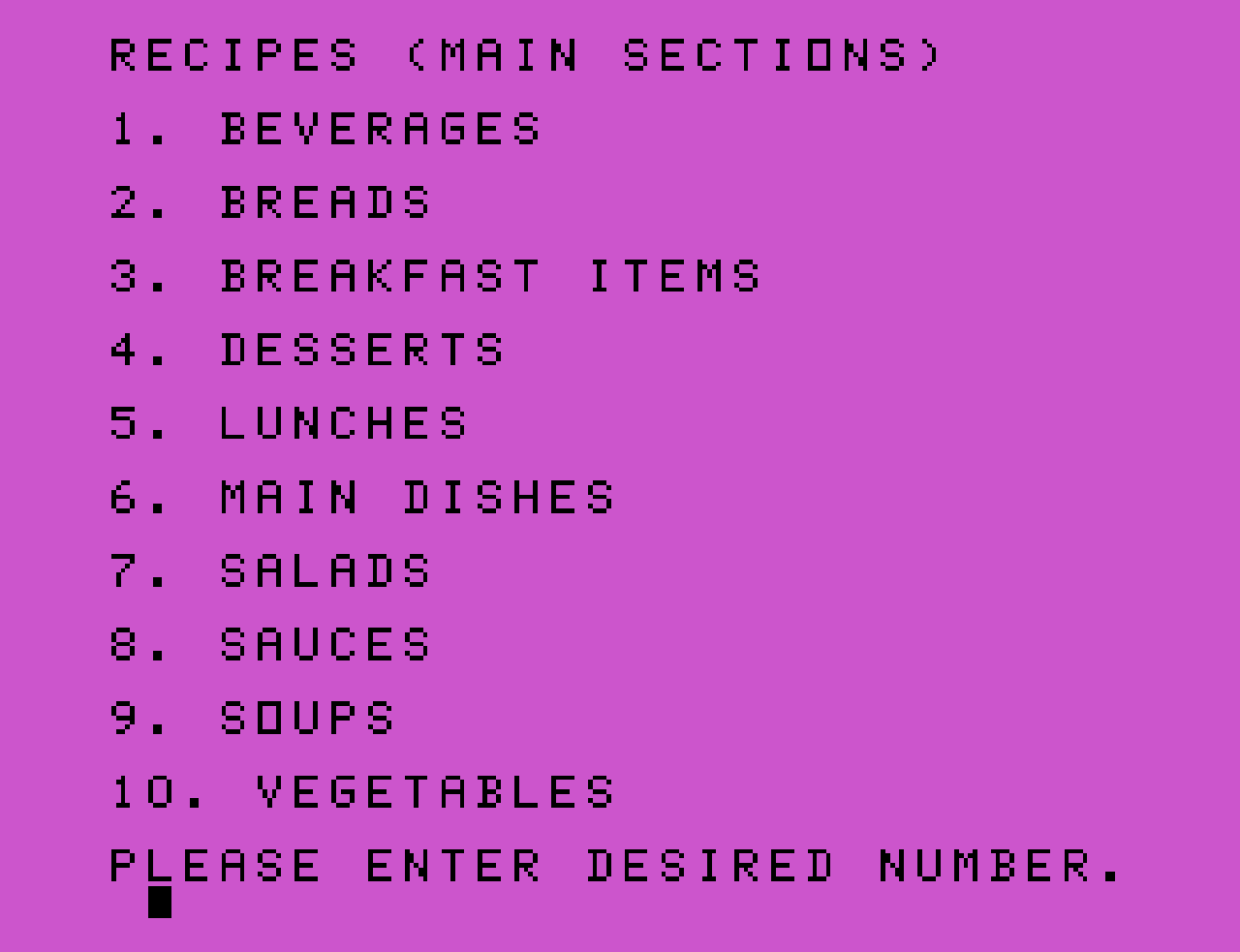

Midjourney seemed to do quite well with the juxtaposition of “gold” and “mountain” when I requested “golden mountain” (with no additional query parameters). Here are the first four “golden mountain” images generated by Midjourney, which you can compare with your own mental picture of a golden mountain from above:

Things get a bit fuzzier and more specious, however, when attempting to render an image based on a more abstract search term. How exactly does one visualize the abstract concept of virtue in the first place? Is virtue a purely moral concept? Is virtue species-specific, as Aristotle held? A horse’s virtues (speed, strength, steadfastness, loyalty, endurance), after all, seem to be rather different than the uniquely human virtues associated with being the rational, political, and social animals that Aristotle claimed that humans are. Even if virtue could be precisely defined, could it be literally visualized, per se, in any case? Nonetheless, Midjourney was able to provide me with the following AI-generated images based on the search term of “virtuous horse”:

It’s unclear exactly what’s going on in these AI-generated images of a virtuous horse. The white horse may connote virtue as a form of purity (in the Victorian sense, perhaps). Whereas the running horse may connote virtue as a strength and power (more Homeric virtues, perhaps). In any case, not only is it unclear exactly which sense(s) of virtue that Midjourney is attempting to invoke, but also it seems that Midjourney is constrained to its (nonetheless remarkable) collection of source imagery, complete with any previous definitional and connotative biases in the sources images, either in the source images themselves or in their alt-text descriptions that presumably are correlated with search terms in a Midjourney query.

These inherent biases get a bit more obvious when searching for “infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being,” which Midjourney apparently (and comically) interpreted visually as some sort of cosmic German scientist/professor: part Freud, part physicist, and part creator of animal life, apparently, judging from one of the following AI-generated images:

It strikes me as unlikely that these AI-generated images of God interpreted as an “infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being” are an accurate reflection of anyone’s concept of God, especially if one’s conception of God is more abstract, but even if one interprets the concept of God more visually, personally, or concretely. On the one hand, this may simply be a weakness inherent to visualizing any abstract concept, which arguably can be done only metaphorically and symbolically. Alternatively, the wackiness of the God-like images above may point to a weakness in the Midjourney system—perhaps improvable through better source imagery, better content tagging, better alt-text descriptions, or better connotative and denotative associations.

Perhaps, though, David Hume was simply wrong about how some of our concepts are formed through empirical association and synthesis. Rationalist philosophers, such as Plato and Descartes, have held that some concepts are innate, unable to be accounted for through experience or the senses. After all, Descartes might argue, we never have any direct experience of infinity, yet we seem to have a substantive concept of infinity that is familiar to us, both mathematically and theologically, even if one doesn’t, strictly speaking, believe in the actual existence of such an “infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being.” If an AI image-generator such as Midjourney is unable to generate a convincing image of God from Hume’s empirical analysis of the concept of God, and if no items of actual experience can be adequately synthesized or augmented to produce the concept of God, perhaps the concepts of “golden mountain” and “infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being” are not as analogous, in terms of the origin of the relevant concepts, as Hume claimed that they were.

In other words, is the disparity between the ease with which we (and Midjourney) picture a golden mountain and the difficulty with which we (and Midjourney) picture a synthetic visualization of God a mere matter of degree and complexity, or is it a result of “golden mountain” and “God” being qualitatively different kinds of concepts, one grounded in experience and one held, as Descartes maintained, innately as a result of pure reason with no empirical basis? While it strikes me as more likely that Hume is actually correct that we can simply “augment” concepts that we do get from experience and sentiment (e.g., power, intelligence, etc.) to form corresponding theological concepts (e.g., omnipotence, omniscience, etc.), it’s not clear at all how this augmentation actually works or how it can be adequately visualized by AI image generators such as Midjourney, except metaphorically as mentioned previously.

It seems wrong to claim that every substantive concept must be able to be visualized, given that some concepts seem so abstract that no possible visualization can capture their essence, and yet it seems that there is much room for improvement for AI text-to-image generators like Midjourney to render increasingly abstract concepts. The pedagogical value in doing so seems immense, especially for the sake of those students who struggle to visualize abstract concepts—whether in philosophy and other humanities, or even in the natural sciences such as theoretical physics and cosmology with their increasingly vocabulary of abstract terminology. Even more exciting, however, may be the possibility of expanding the realm of human consciousness, expression, and experience by finally having the ability to directly experience with our senses those synthetic concepts to which we have hitherto had access only through human imagination, but which are now being brought into the realm of our direct sensory experience in new ways never before possible.

After having indulged myself in some empirical research on AI-generated images based on David Hume’s own examples of synthetic concept-formation, it seems a shame that Hume didn’t live to see his famous golden mountain rendered by Midjourney above. I think it would have made Hume smile, even if he would then likely go down the rabbit hole of trying to get Midjourney to render an adequate visualization of an infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being. Whether it’s a lost cause for today only in practice or forever in principle because of the limitations of visualization (whether human visualization or machine visualization), the limits of empiricism as it relates to concept formation, or the fundamental limits of artificial intelligence is still to be determined as the art and science of artificial intelligence continue to be developed and continue to unfold in the coming years.