The Greatness of Grandfathers: In the Shadow of Greatness

“Thank God for grandfathers,” my maternal grandfather, Roger Forssell, used to say. He never knew either of his own grandfathers, Swedish Parliamament member Johan Forssell and Daniel Jefferson Bogue from Illinois. As a result, my grandfather seemed to take great pleasure from being grandfatherly with his own grandchildren, from helping us out when needed (cosigning for my first car, for example, and giving my cousin Jeff Lehfeldt and me some extra money for food after I spent our food money on a new fishing pole!) to giving advice as only a grandfather can give. And I used to love listening to my grandfathers oft-repeated World War II stories of his time as a B-24 pilot and squadron leader in the South Pacific. (His plane was the Cruisin’ Susan, part of the 531st Squadron of the 380th Bombardment Group of the Fifth Air Force.)

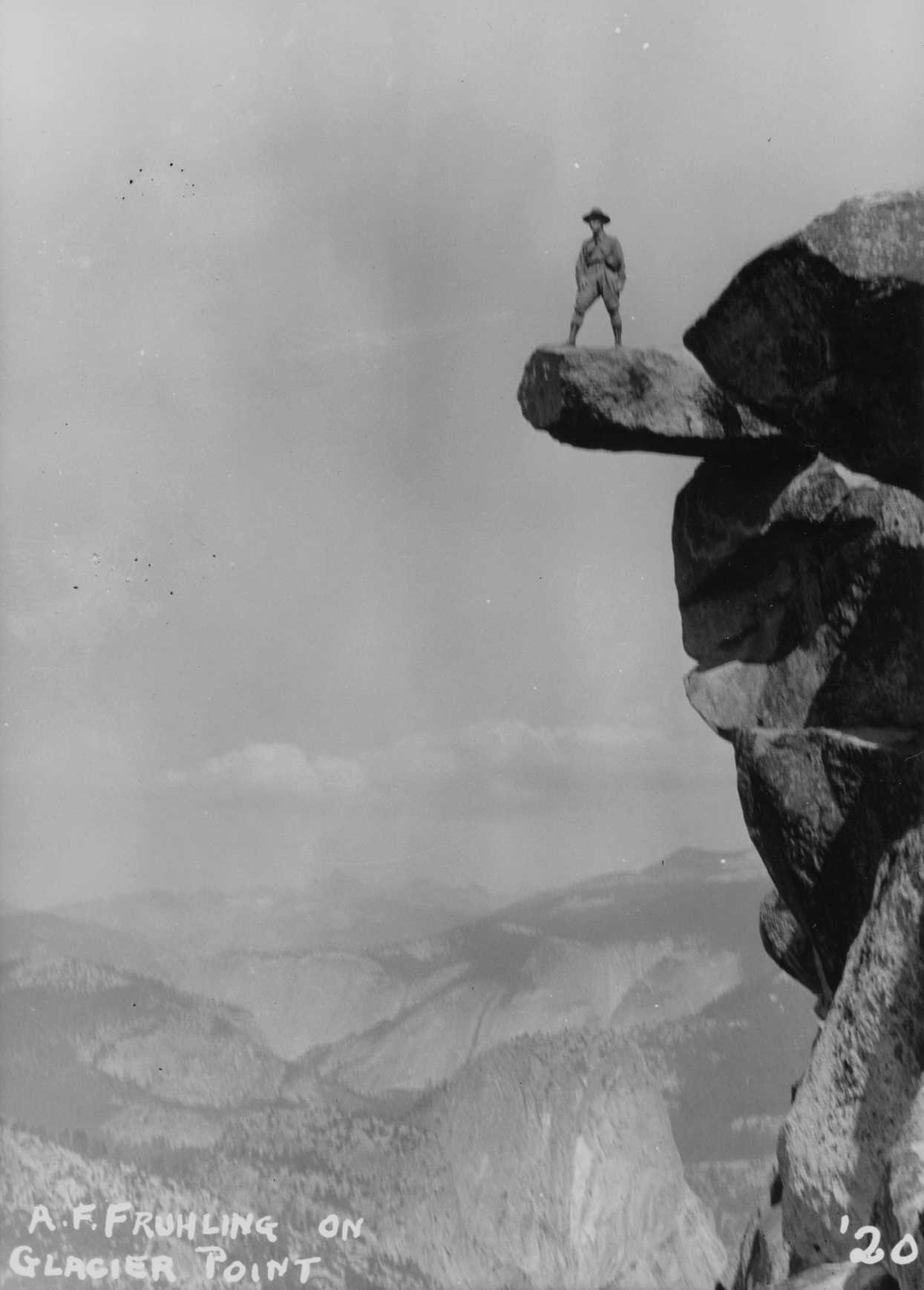

I never knew my paternal grandfather, Reverend Arthur F. Fruhling, who died in 1962, even though my dad tells me that I am quite similar to him in temperament and interests, from hiking to theology to philosophy—perhaps making a case for the fact that at least some aspects of one’s personality and interests are genetic. For this reason, and perhaps because I never knew him, I have always had a certain fascination with and admiration for him, from his epic hiking adventures, such as his two week trek through the High Sierra as recounted in A Trip Through the High Sierra: Along a Portion of What Was to Be the John Muir Trail by Arthur F. Fruhling), to his many, many typewritten and handwritten sermons of which I am still in possession (being the de facto family history archivist that I have become).

There is an interesting literary and cultural tradition of grandsons not feeling as though they are living up to the greatness of their grandfathers (or fathers, great grandfathers, etc., by extension). Roman emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius praised his own father, grandfather, and great grandfather in Book I of his Meditations. Reading the following passages, one can’t help but wonder whether, in reflecting on his own father figures, felt as though he himself wasn’t quite able to live up to the standards they set and the examples they lived and provided for him:

1. I learned from my grandfather, Verus, to use good manners, and to put restraint on anger.

4. I owe it to my great-grandfather that I did not attend public lectures and discussions, but had good and able teachers at home; and I owe him also the knowledge that for things of this nature a man should count no expense too great.

(Roman emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius)

Marcus Aurelius also goes on, at great length, about the virtues of his adopted father, the emperor Antoninus Pius:

16. I learned from my father gentleness and undeviating constancy in judgments formed after due reflection; not to be puffed up with glory as men understand it; to be laborious and assiduous. He taught me to give ready hearing to any man who offered anything tending to the common good; to mete out impartial justice to every one; to apprehend rightly when severity and when clemency should be used; to abstain from all impure lusts; and to use humanity towards all men. Thus he left his friends at liberty to sup with him or not, to go abroad with him or not, exactly as they inclined; and they found him still the same if some urgent business had prevented them from obeying his commands. I learned of him accuracy and patience in council, for he never quitted an enquiry satisfied with first impressions. I observed his zeal to retain his friends without being fickle or over fond; his contentment in every condition; his cheerfulness; his forethought about very distant events; his unostentatious attention to the smallest details; his restraint of all popular applause and flattery. Ever watchful of the needs of the Empire, a careful steward of the public revenue, he was tolerant of the censure of others in affairs of that kind. He was neither a superstitious worshipper of the Gods, nor an ambitious pleaser of men, nor studious of popularity, but in all things sober and steadfast, well skilled in what was honourable, never affecting novelties. As to the things which make the ease of life, and which fortune can supply in such abundance, he used them without pride, and yet with all freedom: enjoyed them without affectation when they were present, and when absent he found no want of them. No man could call him sophist, buffoon, or pedant. He was a man of ripe experience, a full man, one who could not be flattered, and who could govern himself as well as others. I further observed that he honoured all who were true philosophers, without upbraiding the rest, and without being led astray by any. His manners were easy, his conversation delightful, but not cloying. He took regular but moderate care of his body, neither as one over fond of life or of the adornment of his person, nor as one who despised these things. Thus, through his own care, he seldom needed any medicines, whether salves or potions. It was his special merit to yield without envy to any who had acquired any special faculty, as either eloquence, or learning in the Law, in ancient customs, or the like; and he aided such men strenuously, so that every one of them might be regarded and esteemed for his special excellence. He observed carefully the ancient customs of his forefathers, and preserved, without appearance of affectation, the ways of his native land. He was not fickle and capricious, and loved not change of place or employment. After his violent fits of headache he would return fresh and vigorous to his wonted affairs. Of secrets he had few, and these seldom, and such only as concerned public matters. He displayed discretion and moderation in exhibiting shows for the entertainment of the people, in his public works, in largesses and the like; and in all those things he acted like one who regarded only what was right and becoming in the things themselves, and not the reputation that might follow after. He never bathed at unseasonable hours, had no vanity in building, was never solicitous either about his food or about the make or colour of his clothes, or about the beauty of his servants. His dress came from Lorium—his villa on the coast—and was of Lanuvian wool for the most part. It is remembered how he used the tax-collector at Tusculum who asked his pardon, and all his behaviour was of a piece with that. He was far from being inhuman, or implacable, or violent; never doing anything with such keenness that one could say he was sweating about it, in all things he reasoned distinctly, as one at leisure, calmly, regularly, resolutely, and consistently. A man might fairly apply that to him which is recorded of Socrates: that he could both abstain from and enjoy these things, in want whereof many show themselves weak, and, in the possession, intemperate. To be strong in abstinence and temperate in enjoyment, to be sober in both—these are qualities of a man of perfect and invincible soul, as was shown in the sickness of Maximus.

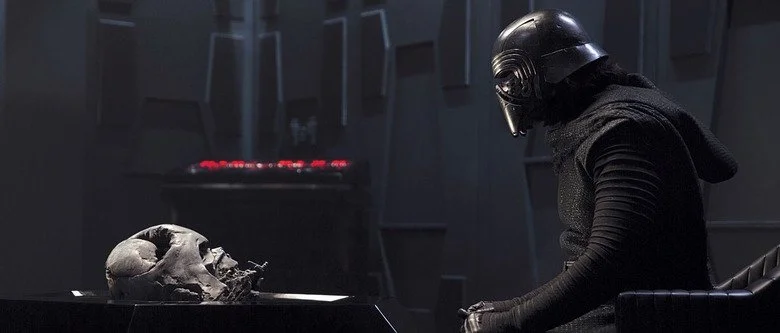

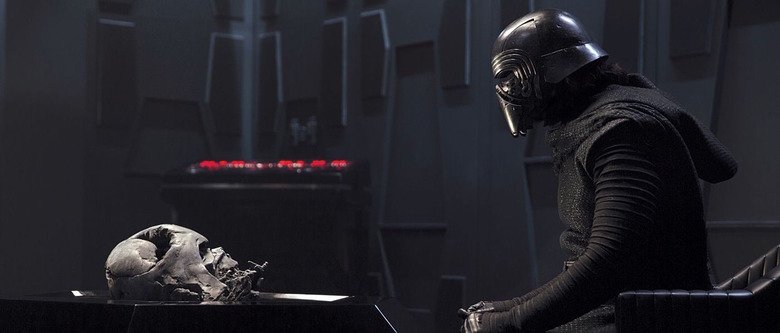

It’s well-known, from classical mythology to modern psychology, that fathers and sons are often at odds with one another. Consider, for example, the relationship between Icarus and his father Daedalus in Greek mythology, or the tragedy of Oedipus Rex by Sophocles and its impact on Freudian psychology. This antagonistic relationship between fathers and sons is well-understood even by the cultural and intellectual lay-person. What gets less attention, however, is the relationship between grandfathers and grandsons, even despite some clear examples from contemporary popular culture. In the film Star Wars: Episode VII — The Force Awakens, for example, the strained relationship between Kylo Ren, the biological son of Han Solo, and his father comes through loud and clear and should be familiar enough to anyone with even a passing interest in either mythology or modern psychology. More interesting and lesser appreciated, however, is the desire Kylo Ren has to achieve the same level of greatness (albeit in a darker sense in alignment with the dark side of The Force) as his grandfather, Darth Vader (a.k.a., Anakin Skywalker). From his mannerisms to the color of his lightsaber to his all-black outfit to his voice-disguised mask and breathing apparatus, it’s clear that Kylo Ren, despite viewing himself as an equal with his grandfather, Darth Vader, is really just a pale shadow or a bad copy who can’t quite live up to the original—perhaps in an ironically dark interpretation of Platonic mythology with an ideal form of darkness and its imperfect instantiations in the physical world that only partake of the original but to a lesser degree. The practical veneration by Kylo Ren of Darth Vader’s mangled and burned mask, to near religious proportions, clearly illustrates the way in which his own grandfather has become a kind of idol, icon, or ideal to Kylo Ren, perhaps to the point of never even fully establishing his own separate identity.

(Kylo Ren venerating the mask of his grandfather, Darth Vader, in Star Wars: Episode VII — The Force Awakens)

Another example of grandfather-veneration in film that comes to mind is the relationship between historian Benjamin Franklin Gates (played by Nicholas Cage) and his grandfather, John Adams Gates (played by Christopher Plummer) in National Treasure. Despite a clearly antagonistic with his father (Patrick Henry Gates, portrayed by John Voight), the course of Benjamin Gates’s life and the adventure depicted in the film were set in motion by his grandfather who first provided the goal, history, and meaning behind the quest to find the Gates family’s object of veneration—the lost treasure of the Knights Templar and the Freemasons. Benjamin Gates is more his grandfather’s grandson than his father’s son. In this case, however, the grandson actually supersedes the grandfather (and certainly the father, who wants nothing to do with the family quest) insofar as he actually succeeded in finding, through his own ingenuity, the lost treasure that his grandfather had only dreamed of finding.

(Christopher Plummer and Hunter Gomez in National Treasure)

Expecting to have no biological grandchildren of my own, it’s unlikely that anyone will ever sing praises of my own many virtues—or even my noteworthy vices, as the case may be!—as Marcus Aurelius sang the praises of his grandfather Verus’s virtues. Such is the price to pay for what fate and human free will have dealt me in life. Perhaps this is why I feel so driven to write and write and write—to leave something of myself behind, given that I likely won’t have any direct descendants of my own to remember me, to speak well of me when I am dead and gone, or who desires to imitate or emulate me in some fashion down the road. And perhaps this is why I feel such a strong pull toward genealogy and family history, to make sure that the virtues of my own ancestors, grandfathers and otherwise, both nearly and distantly related, aren’t forgotten—even if I, despite my many accomplishments and strengths, am and will ever be only a pale shadow of their greatness and virtue.