What Counts as Good Philosophical Writing?

We philosophy teachers sometimes present too narrow a picture of what counts as philosophical writing. We teach our students to write short response papers and longer philosophical essays, all through the lens of argument analysis. But philosophical writing can be much richer than argument analysis and essays, much more than a well-structured argument and a thesis statement.

Even a cursory look at the history of philosophy will reveal a wide variety of philosophical forms and approaches to writing philosophy, only some of which fall into the paradigm of philosophical essays that most students are commonly taught to pursue in their own philosophical writing. Think of the philosophers in the history of philosophy, for example, who have written in the following styles and forms:

Essays

Journal articles

Books

Treatises

Diaries / personal journals

Letters

Aphorisms

Poetry

Dialogues

Blog posts

Although students may be exposed to these alternative forms of philosophical writing in the materials they are required to read in a typical Introduction to Philosophy class, very seldom are they encouraged to experiment with these alternative forms in their own writing. When, for example, was the last time, if you are a philosophy teacher, that you required your students to write a philosophical poem or to keep a daily journal? If you are or were a philosophy student, have you been asked to write your own philosophical dialogue or a series of aphorisms to capture the essence of your thoughts on a particular topic or philosophical issue?

I suspect that the number of students asked to try out these alternative forms of philosophical writing is quite small. In requiring standard-form philosophical essays, we run the risk of depriving our students of the freedom to experiment with their own thoughts and their own words, of the liberty to experiment with the way in which form itself can be part of the message, such as the way in which my chosen medium of philosophical blogging is actually part of my commentary on and criticism of the prescriptiveness of mainstream academic writing, and of the academic publishing industry as a whole.

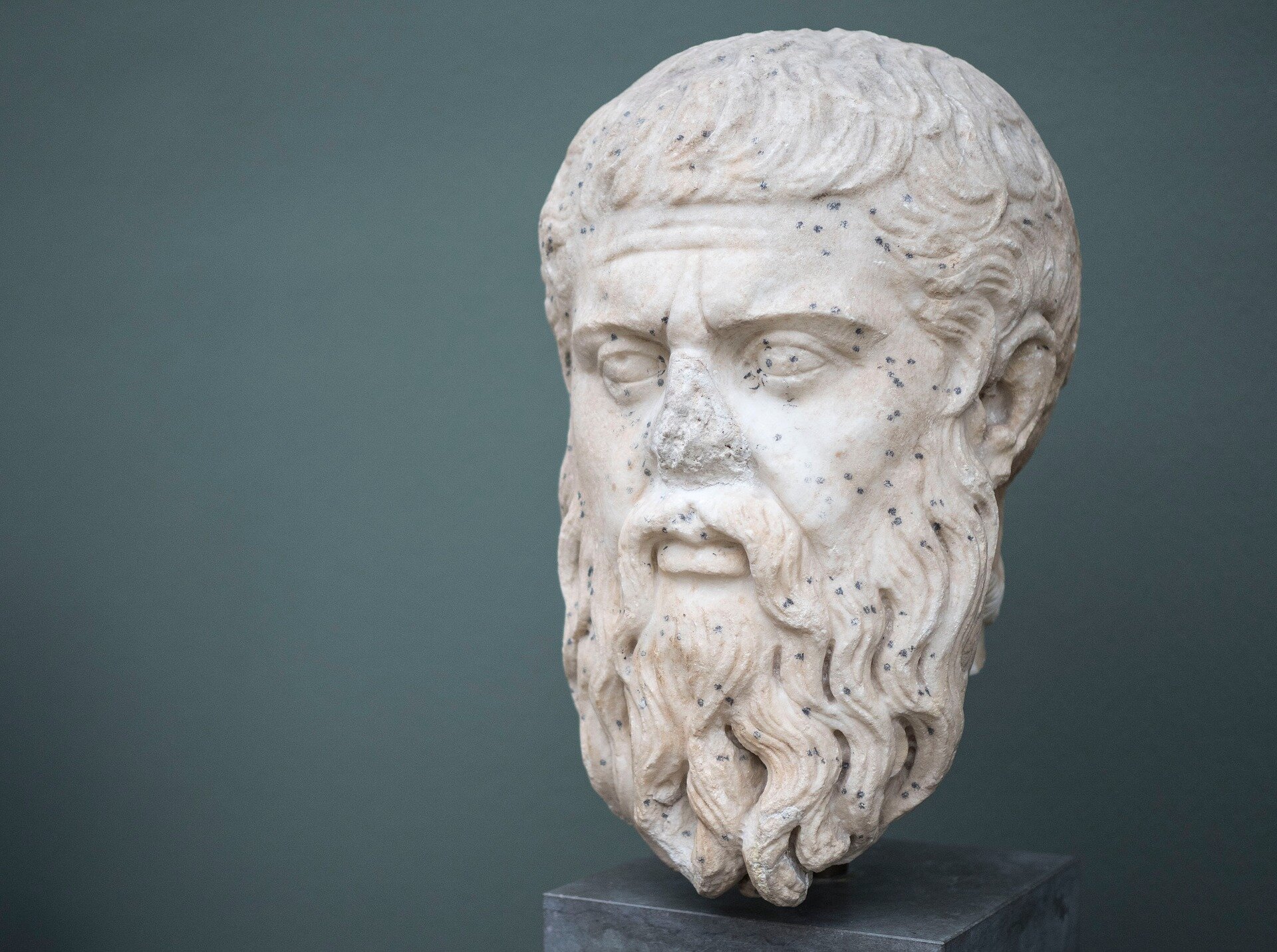

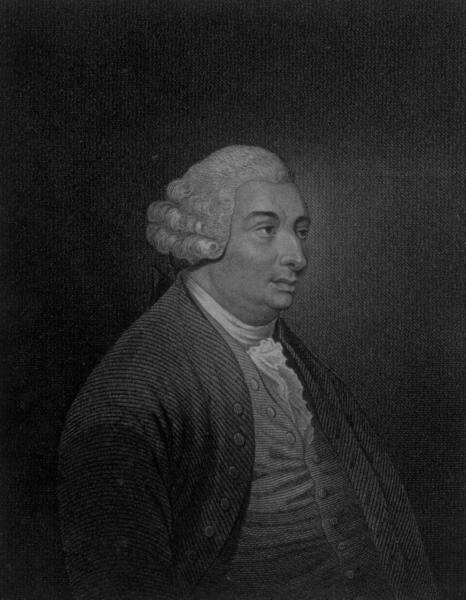

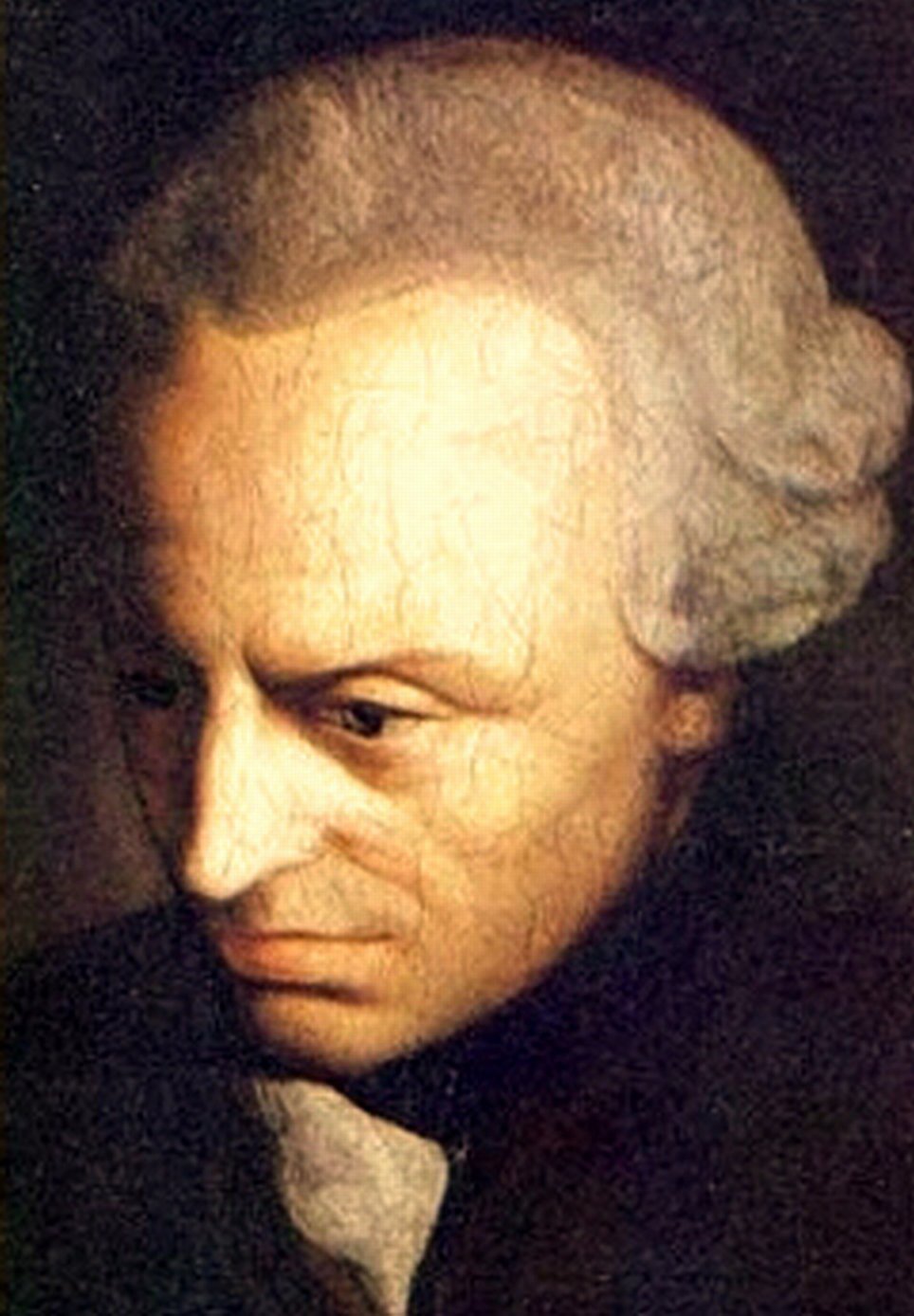

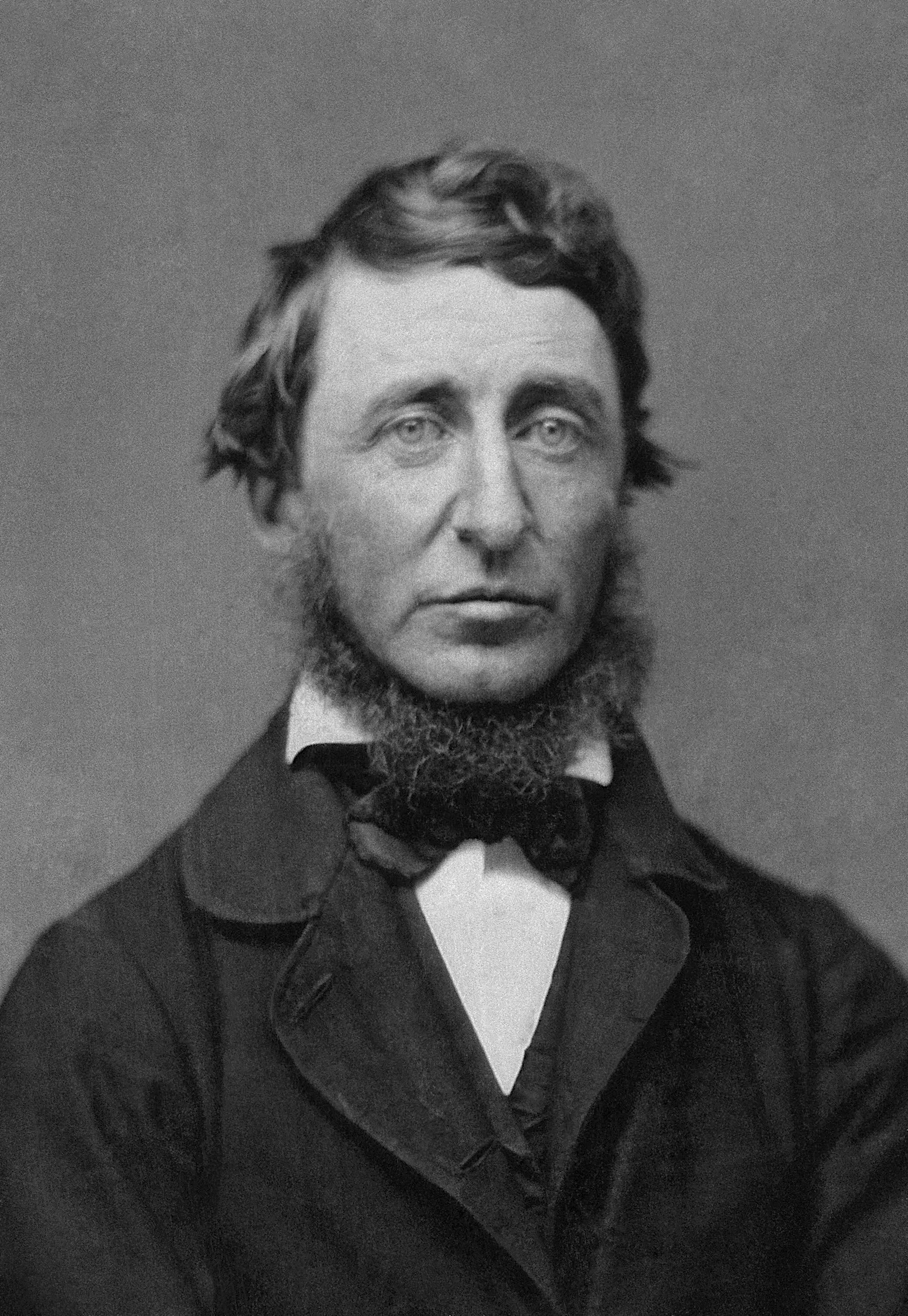

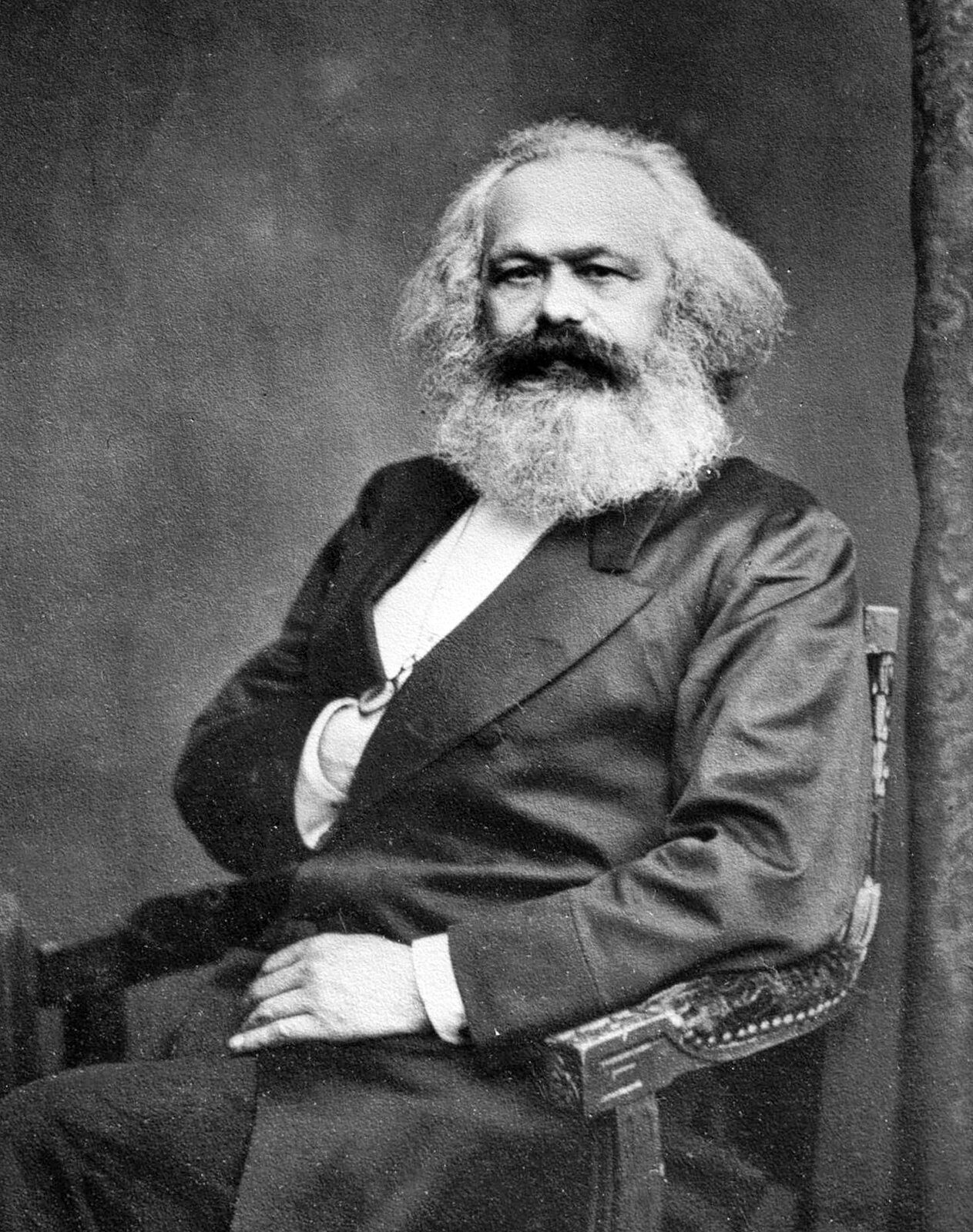

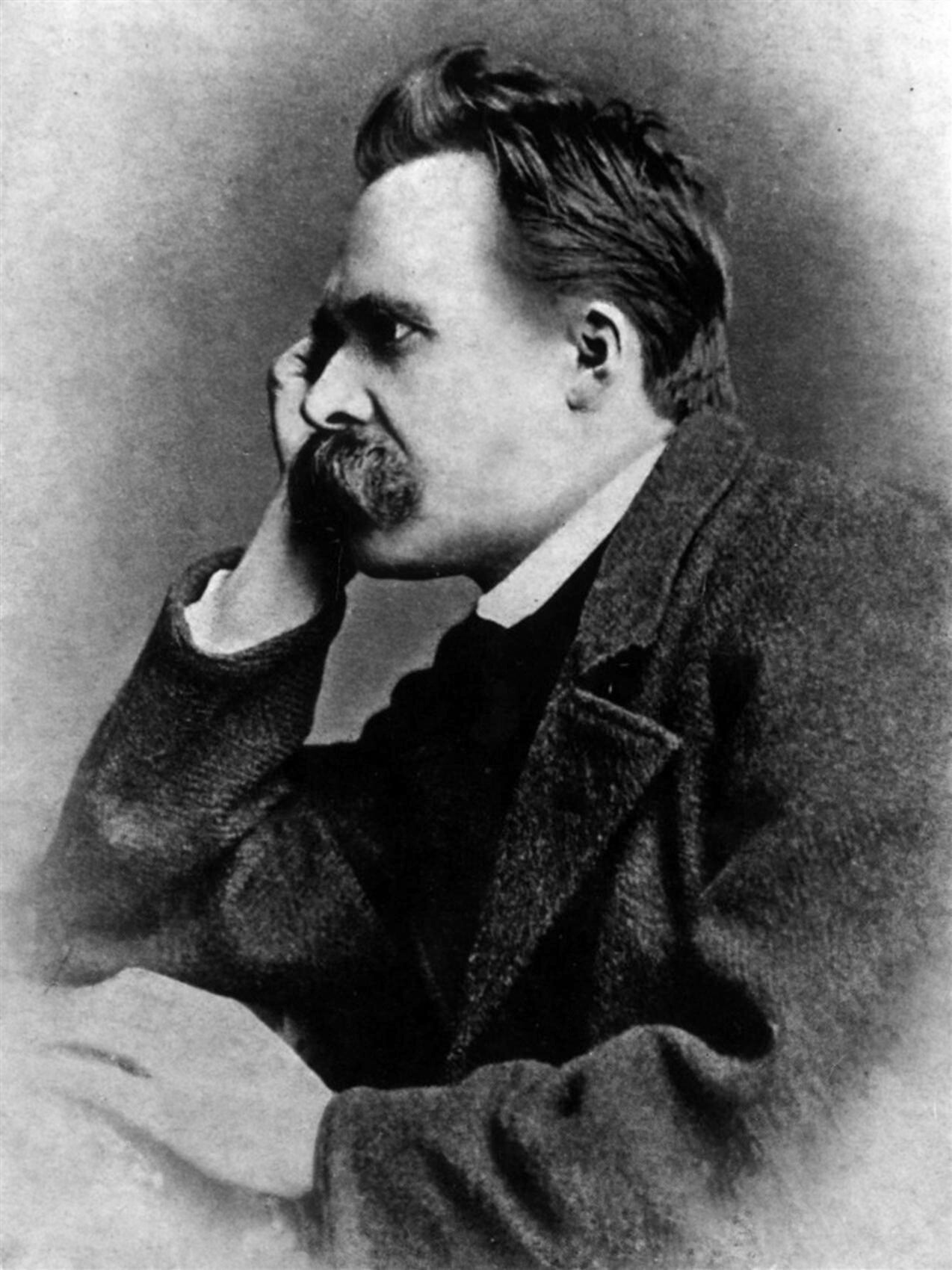

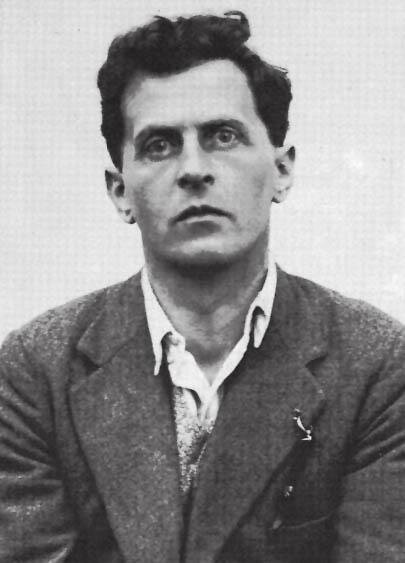

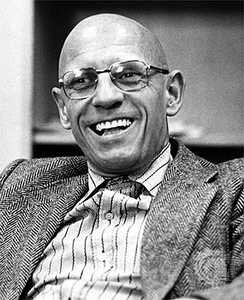

Naturally we want to help train our students to do the type of writing that they will be expected to do throughout the rest of their academic and professional careers, boring as that writing may be. It’s worth noting, however, that the philosophers who made the biggest impact on the history of philosophy were often those philosophers who broke with traditional forms (especially those of their teachers) and developed their own styles of writing. Think, for example, of the stylistic differences between the following philosophers, each of which I consider to be a linchpin or a turning point in the history of philosophy, or at least a philosopher with a radically unique style:

What a philosophical and literary tragedy it would have been if each of these philosophers had been constrained to writing only the kind of uninspired, hegemonic philosophy essays we require of our students! For me, part of the joy of reading the great philosophers is immersing myself in their literary style and gestalt, not merely in their premises and conclusions—seeing the world and all of reality through their own unique eyes, following the free-flowing nature of their thoughts like water running downstream to its inevitable conclusion based not just no differing conclusions but on differing personalities, styles, linguistic quirks, and individual perspectives—all while bucking the trend of philosophical writing as it had been previously known.

No, we should not be teaching our students to write the same way, as if the standard-form philosophical essay were some kind of Platonic ideal or carried by Moses down from Mount Sinai. We should actively be encouraging students to push the limits off their own writing and thinking, and to develop their own literary style, even if that style flies in the face of philosophical writing as we know it. After all, by the time we philosophy teachers make our way through grad school and become mentors and teachers, the world, culture, literary styles, and trends have changed all around us, and we’ve had our noses too much in the books to notice that we’re already dinosaurs, or how rigid and inflexible we’ve really become.

The vision I’m presenting here is an interpretation of the history of philosophy as a form of literature and a form of creative writing, even if philosophical argumentation and logical soundness remain at the heart of philosophical writing as opposed to literature and fiction proper. There is far more overlap, however, between other genres of writing and good philosophical writing, especially of the groundbreaking or game-changing variety in the history of philosophy, than philosophers generally acknowledge or would usually like to admit.

Perhaps this is why the version of the history of philosophy that I present in my Introduction to Philosophy class is epic in scope. I want students to immerse themselves not only in philosophical argumentation but in the drama of philosophy and in its many beautiful forms of writing for their own sake, all in the interest of helping students experiment with their own writing and acquire their own voice that they will carry with them and keep developing over the course of their entire lives. Anything less that we require of our students as young philosophers and writers is a waste and a disservice, both to them and to the history of philosophical writing itself that we hold so dear.