NFTs, Cryptocurrency Paychecks, and Play-to-Earn Gaming: Hyperreal Employment in the Hyperreal Economy

French philosopher and sociologist Jean Baudrillard claimed that we now live in a hyperreal society in which the simulated and the real have become so intertwined that it’s no longer possible, even in principle, to distinguish between the two. Whether in technology, economics, or popular culture, the ongoing intermeshing of the simulated and the real has resulted in a pervasive hyperreality that has crept into almost every area of contemporary life.

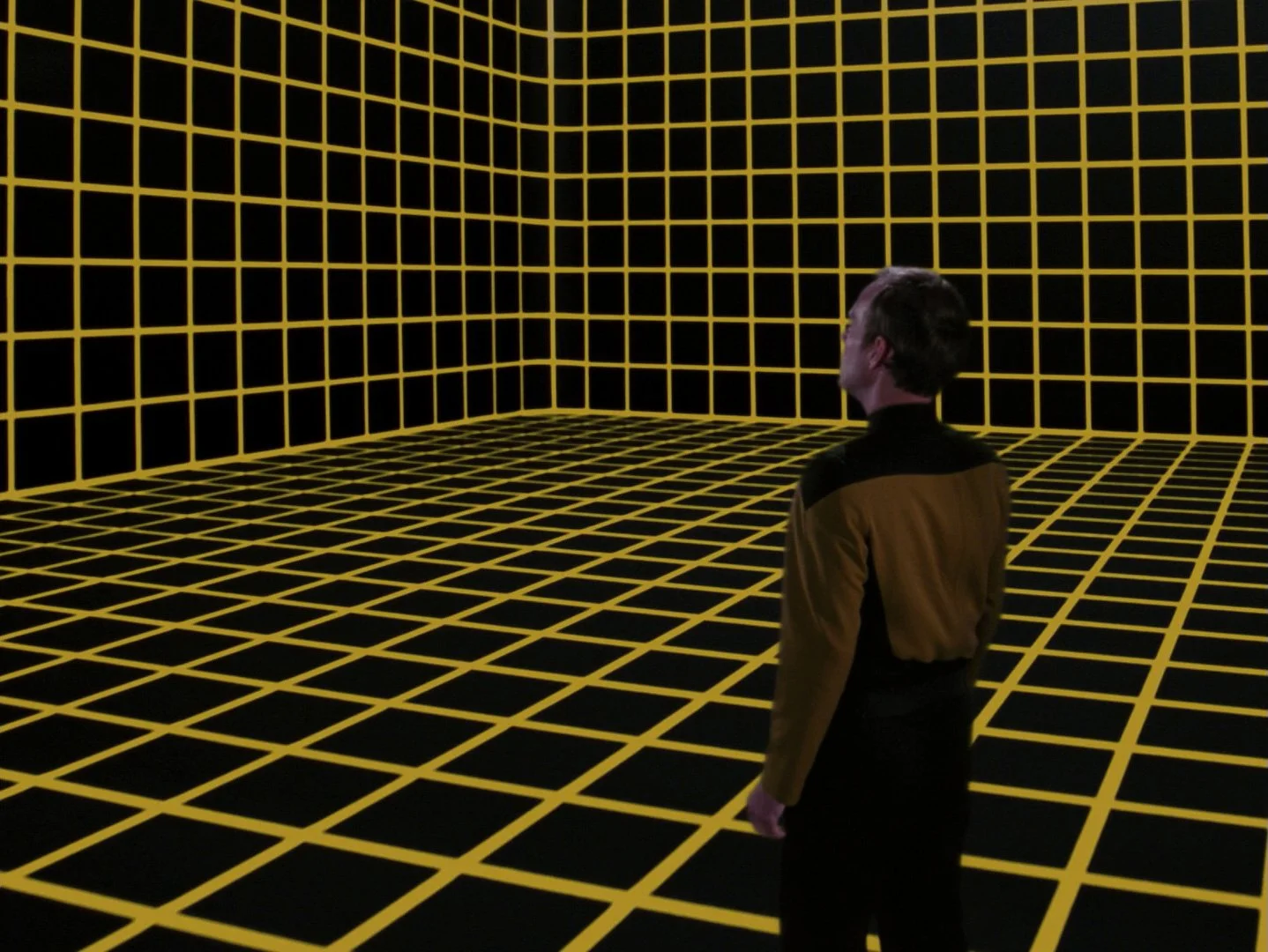

Earlier this week I had what is perhaps the most hyperreal job interview I have ever had. The interview was for an instructional designer position (which one might argue is already hyperreal by definition) for a video game company whose name I will omit for reasons of simulated propriety. Not only was the interview conducted by online videoconferencing (Google Meet, to be exact), itself a kind of hyperreal form of the traditional job interview, but the job itself is a remote position. Working remotely is not exactly new to me, as I’ve been working remotely from home, full time, for nearly seven years. Remote work, of course, is hyperreal through and through!

The remote position isn’t what caused me to reflect on the hyperreal state of employment, however. Sometimes the world around us changes so much, both so rapidly and so gradually simultaneously, that one simply doesn’t notice just how much the world has changed until one is confronted with a tidal wave of hyperreality and novelty all at once. That’s what happened to me during this job interview. For this company was no mere video game company; it is a highly speculative company deeply immersed in the emerging world of cryptocurrency, NFTs (non-fungible tokens), and esports. Even a brief look at some of the distinguishing characteristics of this company’s business model reveals just how deeply interwoven the hyperreal has become in today’s employment and business worlds:

A pay-to-earn gaming model in which players earn cryptocurrency for achievements in-game, a virtual “currency” (in irony quotes) that can be exchanged for so-called “real” currency in turn. (Notice that it’s already nearly impossible to distinguish “real” currency from “simulated” currency where cryptocurrency is involved.)

Players obtain and/or purchase in-game NFTs (non-fungible tokens), digital assets that are owned—in some hyperreal, not-real-but-not-fake-either sense of the term “ownership”—by the players.

The company is planning to start its own “university” (in heavy irony quotes and in a definite hyperreal sense of the word “university”) to get players up to speed on the company’s business and gaming models—hence the need for an instructional designer in the first place: a hyperreal instructional designer building hyperreal learning content for a hyperreal “university” for a hyperreal gaming company.

The company is based in a foreign country—Singapore—in which the economy has already become more deeply intertwined with the cryptocurrency model than it has in the United States. (One might further claim that this type of globalization, already decades in the making, is yet another form of hyperreality.)

Because this small company’s workforce is a highly distributed and global one, the company pays its employees with the cryptocurrency Ethereum, noted for its relative stability compared to other forms of cryptocurrency, albeit in some hyperreal—not quite real, not quite artificial—sense of “stability.”

It was clear to me that the company is still in the seed-funding, venture capital stage, which means it is, at very best, years and years away from being “profitable” in any traditional sense.

Note, however, that one can’t help but use the irony-quotes of hyperreality when discussing “profitability” in the modern economy. Speculative investment capital in speculative companies “innovating”—again in irony-quotes—on speculative, hyperreal forms of economic novelty such as NFTs and cryptocurrency, may produce a “real” company that draws “real” investors and “real” gamers,” that provides “real” paychecks to its employees, and that allows the company to later be sold for a profit to the “real” highest bidder. Where the line should be drawn between the real and artificial is—almost but not quite, given the volatile nature of speculative investments of all forms—irrelevant.

I can’t deny that I’ve been itching to get involved in the video game industry for quite a long time, having been a lifelong gamer myself and having dabbled in various forms of gamification in educational technology and instructional design. I’m also morbidly curious just how far one can ride such a blatantly hyperreal economic wave, especially when the hyperreal elements have become so pervasive that they no longer cause anyone at the company but me to flinch!

Having ridden a prior wave of educational technology during my time at Aplia, I can say with some confidence that a wave, a hyperreal wave or otherwise, is just that—a wave, one that will inevitably rise and fall like so many other trendy waves in the increasing trend toward the hyperreal. Were I to get the job at this company, still far from a “reality,” I can’t wait to see the look on my Idaho-based tax accountant’s face next year when I need him or her to figure out how to report my cryptocurrency earnings for tax purposes!

Other, perhaps, than the highly speculative nature of such industries and companies, there is nothing inherently wrong with new trends, new concepts, new technology, new business models, etc. Baudrillard himself would have been the first to say that the hyperreal itself should not, ipso facto, be subject to moral judgments. In fact, any attempt to criticize hyperreality for being hyperreal is just another artificial attempt to coax the hyperreal back into the domain of the “real,” which has already been so far subsumed into the hyperreal that it no longer carries any distinct meaning above and beyond the real’s role in the hyperreal—perhaps especially where speculative technology and the speculative economy intersect!

One might choose to look at the hyperreal in Hegelian terms, with the “real” being analogous to Hegel’s “thesis,” the artificial or simulated being analogous to Hegel’s “antithesis,” and Baudrillard’s sense of hyperreal being analogous to Hegel’s “synthesis”—a hyperreal synthesis that itself has become the new “real,” the new “normal,” and the new “standard” for us today. As Hegel pointed out, the synthesis becomes the new thesis, just as Baudrillard claimed that the hyperreal has already become the new “real.”

All this talk of hyperreal employment and the hyperreal economy has me yearning for something more “real,” admittedly. But the same dissolving line between the real and the artificial, resulting in the hyperreal, has pervaded and is present in nearly every aspect of contemporary life. Later today I will check my email (a communications simulacrum), text my girlfriend to see how her work day is going (a relationship simulacrum), begin another philosophy blog post (an authorship simulacrum), do some prep-work for the online ethics class I’m teaching next semester (an educational simulacrum), spend some time playing World of Warcraft (an entertainment simulacrum, speaking of video games, with a hyperreal simulacrum of social interaction to boot!), check on my investments (in whatever direction their hyperreal valuation on the New York Stock Exchange has driven them today!), and so on.

At point do we merely throw our hands up and bow to the absurdity of the hyperreal world in which we have found ourselves—in which we were “thrown” into, as existentialist philosophers Heidegger and Sartre might have said? I have to admit that it does make me want to dive into one of these highly speculative pay-to-earn video games like the ones produced by the company I interviewed with this week, if only to see what the fuss is all about. Perhaps I could even earn a few hyperreal cryptocurrency units while I am at it—immediately to be exchanged for so-called “real” dollars, of course. The very concept of “real” is already beginning to feel charmingly anachronistic, isn’t it? Go ahead and admit it, you champions of the so-called real! As the saying goes, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.”—or as we might rightly put it today, “When in the hyperreal, ….”