The Menagerie: Escapism in Star Trek and Philosophy

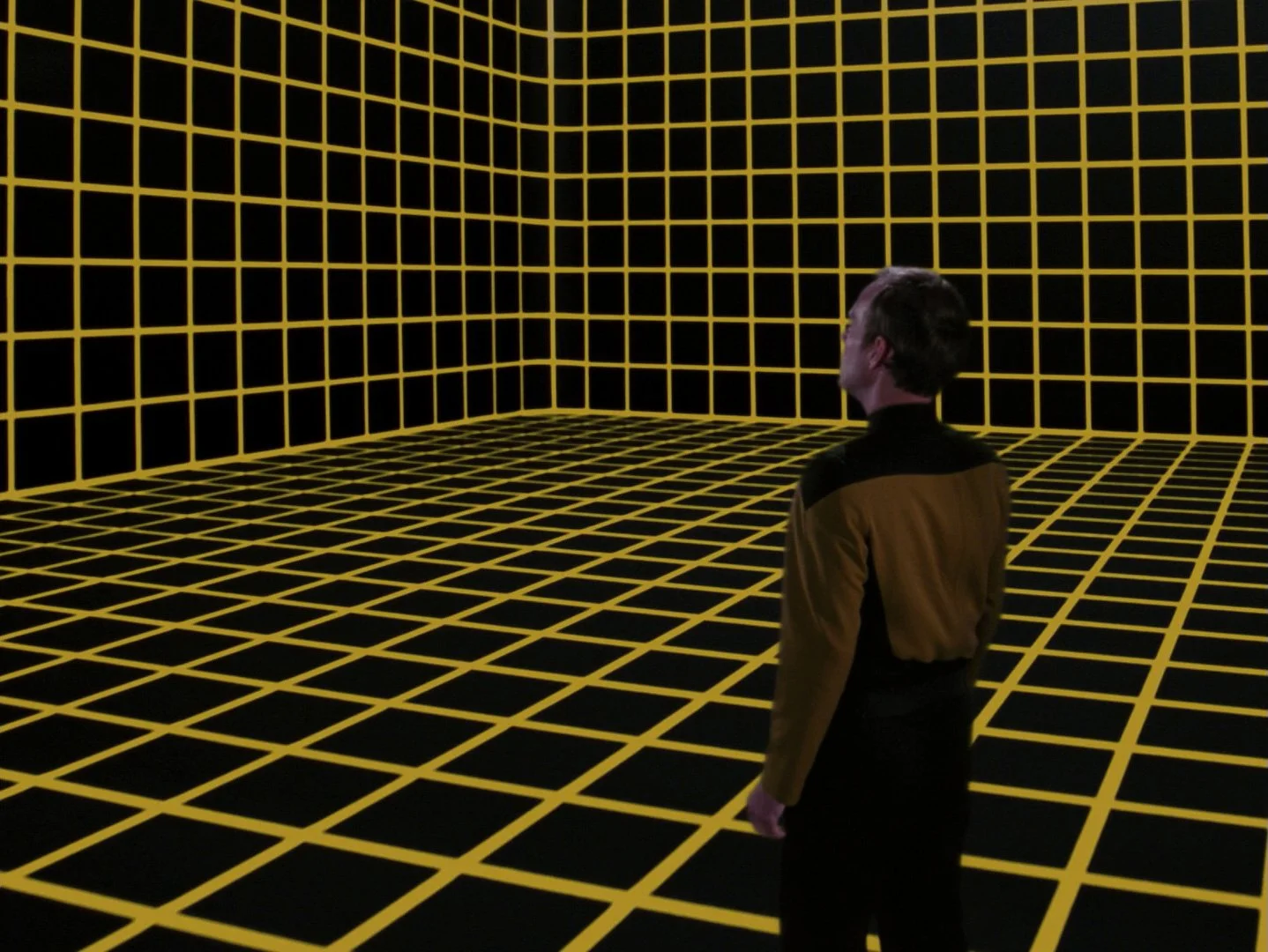

(Lieutenant Reginald Barclay in “Hollow Pursuits,” Star Trek: The Next Generation, Season 3)

Fans of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Voyager are familiar with the character of Lieutenant Reginald Barclay, who is most well-known for his escapism, retreating into a fantasy world of his own imagination via the artificial environment of the holodeck. At one point, in one of the character’s appearances on Star Trek: Voyager (“Pathfinder”), Lt. Barclay goes so far as to say that he’s lost himself in Voyager, an on-the-nose reference to the danger of fandom of all sorts—losing oneself and losing touch with reality in favor of one’s fantasy realm of choice.

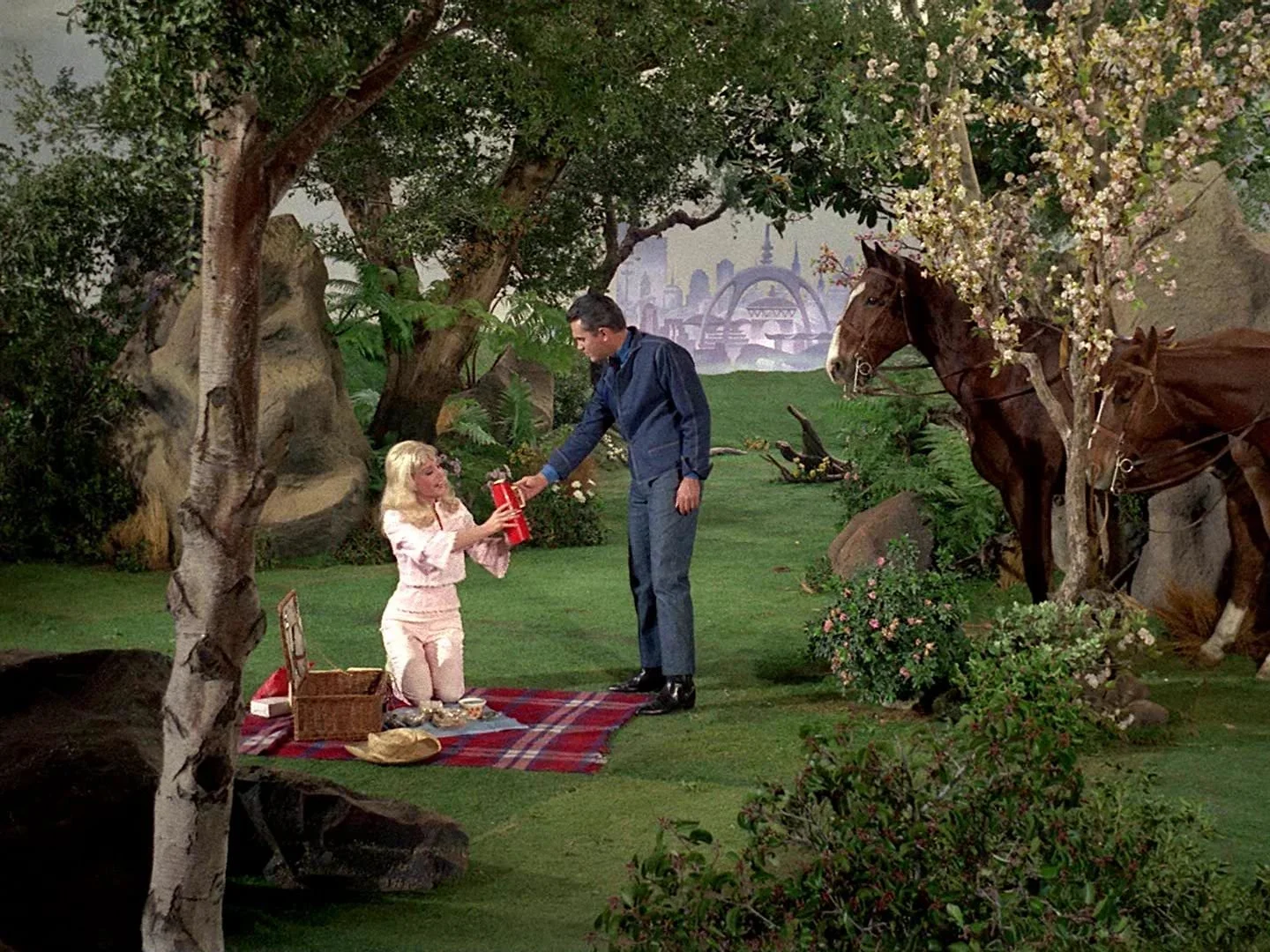

In the Star Trek universe this from of escapism dates all the way back to the unaired pilot of Star Trek: The Original Series, “The Cage,” in which Captain Christopher Pike is offered a life of leisure in a paradise of illusion created by the Talosians. Captain Pike ultimately realizes the dangers inherent in escapism that seeks to avoid the challenges and the vicissitudes of real life:

“It's funny. It's about twenty four hours ago I was telling the ship's doctor how much I wanted something else not very different from what we have here. An escape from reality. Life with no frustrations. No responsibilities. Now that I have it, I understand the doctor's answer. You either live life, bruises, skinned knees and all, or you turn your back on it and start dying.” (Star Trek: The Original Series, “The Cage”)

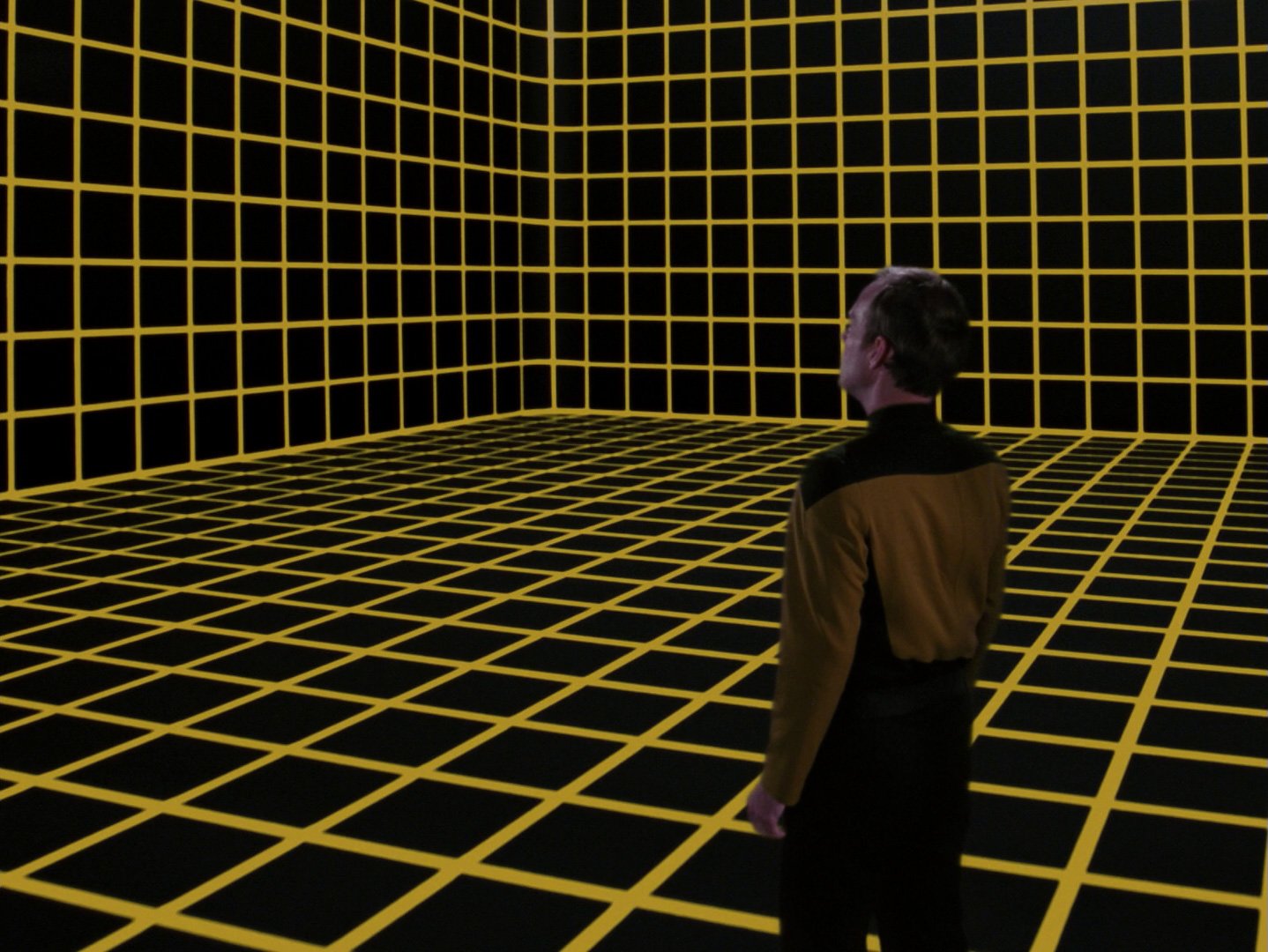

(The illusory paradise created for Captain Pike by the Talosians in “The Cage”)

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche likewise warns against the dangers of seeking refuge from the brute-force reality of physical human existence in any form of philosophical or religious escapism. While escapism in the Star Trek universe is often technological (e.g., holodecks, Unimatrix Zero, etc.), escapism for Nietzsche could be categorized as idealogical. Humans seek refuge from life in the afterlife, whether religious (e.g., heaven in Christianity) or philosophical (e.g., Socrates’s arguments for the immortality of the soul in Plato’s Phaedo dialogue).

Any general theory of human nature can be thought of as a kind of escapism—avoiding taking responsibility for one’s own life and choices by relegating such responsibility to “human nature,” whether conceived of in biological, psychological, or sociological terms. We claim that human suffering has meaning because of its place in some cosmic order or plan. And we explain away all manner of human behavior with behavioral theories of all sorts, in nearly every discipline of thought.

At worst, this kind of philosophical, religious, or idealogical escapism can have a kind of averaging effect, according to Nietzsche, serving only to limit human potential and possibilities instead of promoting them. One of Nietzsche’s successors, existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, claimed that any generalized account of human nature, or of the cosmic or divine order of things, can be used as an excuse preventing people from taking full ownership of their own lives and from having full recognition of their own radically free will. Almost paradoxically, escapism leaves one even less free than the things in life one may seek to escape; the refuge from life becomes the prison, as seen in the way in which Christopher Pike’s illusory reality created by the Talosians is really just a glorified prison cell or zoo cage—fit for animals, perhaps, but ultimately undignified for a human being. Nietzsche is quite critical of the taming of humankind by means of any philosophical, religious, or psychological escapism:

“To call the taming of an animal “improving” it, sounds almost to our ears like a joke. He who knows what goes on in menageries, doubts very much whether an animal is improved in such places. It is certainly weakened, it is made less dangerous, and by means of the depressing influence of fear, pain, wounds, and hunger, it is converted into a sick animal. And the same holds good of the tamed man whom the priest has “improved.” … He looked like a caricature of a man, like an abortion: he has become a “sinner,” he was caged up, he had been imprisoned behind a host of appalling notions. He now lay there, sick, wretched, malevolent even toward himself: full of hate for the instincts of life, full of suspicion in regard to all that is strong and happy. In short a “Christian.” In psychological terms: in a fight with an animal, the only way of making it weak may be to make it sick. The church understood this: it ruined man, it made him weak—but it laid claim to having “improved” him.” (Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols)

Nietzsche’s reference to a menagerie here is clearly what Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry had in mind in the title of the two-part episode “The Menagerie,” which features flashbacks to Christopher Pike’s time in the Talosian “experiment.” Despite the Talosians’ attempt to tame Captain Pike into submission—either through pleasure, pain, or psychological conditioning—the human spirit in the man Christopher Pike, the yearning to be more than a mere animal, more than a mere pig rolling in the mud of illusory pleasures, as John Stuart Mill, that champion of the higher-level human pleasures, might have called it, more even than a mere cog in the Starfleet machine, is an irrepressible voice in the chorus of Captain Pike’s mind and spirit. We cannot escape this human yearning for meaningfulness in the real world, with all its struggling, joys, and sufferings, any more than we can escape our own eventual demise, as the ancient Stoics knew all too well.

This irrepressible drive toward the authentic and the real is described by Fyodor Dostoyevsky as well, a drive that thwarts any attempt at escapism and bends the bars of any sociological, psychological, religious, or philosophical prison cell for the mind:

“Even if man really were nothing but a piano-key, even if this were proved to him by natural science and mathematics, even then he would not become reasonable, but would purposely do something perverse out of simple ingratitude, simply to gain his point. And if he does not find means he will contrive destruction and chaos, will contrive sufferings of all sorts, only to gain his point! He will launch a curse upon the world, and as only man can curse (it is his privilege, the primary distinction between him and other animals), may be by his curse alone he will attain his object--that is, convince himself that he is a man and not a piano-key!” (Dostoyevsky, Notes from the Underground, Chapter VIII)

Just as the human spirit cannot be tamed by external means or conditioning without the kind of perverse ejaculations of individuality seen both in Star Trek (“The Cage” and “The Menagerie”) and in Dostoyevsky, neither can the reality of life be avoided by any form of self-induced fantasy delusions—or religious or philosophical escapism. Any pleasure we obtain in our escapism is ultimately lesser than the pleasures of real life with all its pain. And any sufferings endured during escapism are ultimately meaningless compared with the rich tapestry of meaning be found in actual human suffering and struggle in the real world. Escapism is a rejection of meaning. Nihilism, it follows then, is not a lack of meaning in the real world but instead a rejection of the meaning found in the real world—both its joys and accomplishments, its struggles and its pains—by means of escape to the perceived but ultimately vacuous meaning to be found in one’s fantasy refuge.

It’s no accident, then, that Lt. Barclay’s character is named “Barclay,” for George Berkeley (pronounced “Barclay”) was the philosopher of illusions, claiming that what appears to us to be an external reality filled with independently-existing physical substances is really just non-physical ideas in the mind of some omni-perceptive God, a classic case of philosophical and religious escapism if there ever was one! But just as George Berkeley, a mere human—even a philosopher-human!—must ultimately give in to his own physiology and have lunch (or sex, for that matter), his namesake Lt. Barclay in Star Trek must ultimately leave the holodeck and rejoin his shipmates on a real adventure. Life cannot be lived in a holodeck (despite Nog’s ultimately self-defeating but post-traumatic attempt to do so in the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode “It’s Only a Paper Moon”).

We, too, must have the courage to face human reality itself, with all its vicissitudes and moods. We cannot seek refuge in any philosophical, religious, moral, psychological, sociological, technological, or fictional illusions. Life must be lived, for a life lived only in an illusory menagerie of the mind, or with one foot already in some theoretical afterlife, is no life at all!