Philosophy and Film: Postwar Decadence, Nihilism, and the Search for Authenticity in Breakfast at Tiffany's

I recently watched the classic Audrey Hepburn film Breakfast at Tiffany’s for the first time. While I didn’t really know exactly what to expect, Breakfast at Tiffany’s was definitely not what I expected. I had expected some degree of glitz and glamour from the title card and movie poster of the film, but I hadn’t realized that Breakfast at Tiffany’s is actually an existentialist film about the search for meaning in the context of postwar decadence and nihilism of mid-20th-century American society.

The link between decadence and nihilism is not an obvious one. After all, shouldn’t it be easy to find meaning in one’s life in a time of material affluence, such as were seen in the decades immediately following the end of World War II? Yet Breakfast at Tiffany’s depicts the kind of nihilistic affluence that one would expect in any materialistic culture: endless parties, jewels, consumption, and pretensions—complete contentment with the meaninglessness of their existence on the part of the affluent party-goers with whom Audrey Hepburn’s character, Holly Golightly, seeks to ingratiate herself. Even the name “Holly Golightly” is a nod to the frivolity of the hollow aims Holly sets herself about for the first two thirds of the film. Her name betrays that she and her contemporaries have all but abandoned the quest for deeper meaning beyond the endless stream of nightlife revelries. Holly even studs herself with costume jewelry instead of real diamonds, because real diamonds would simply be too authentic in the meaningless activities and pseudo-relationships with which Holly surrounds herself on a nightly basis and thus serve as a mirror for her own initial shallowness.

Even the most soulful character in the film, the promising young author Paul Varjak, played by George Peppard, has seemingly succumbed to the nihilism of the times, convincing himself that he can be content and happy as a kept man for his patron and implied lover, 2E Failenson (Patricia Neal), whose name is equally on-the-nose, a sign of the failure of the quest for meaning to be found only in the context of real relationships with real authenticity. In Breakfast at Tiffany’s, it’s a sign of the times that even the most authentic of characters must content him- or herself with a simulacrum of a relationship—a relationship of convenience and shallowness over depth and emotional authenticity, the practical fringe benefits of the exchange of sexual intimacy for patronage as a writer aside.

For many people, human relationships aside, pets are a reliable source of meaning, warmth, companionship, and real love. Yet Holly Golightly refuses to be attached even to her not-quite-pet cat, calling him simply “Cat,” again because a real name would imply real connection and perhaps real risk of emotional attachment that Holly seemingly yearns for but for which she is not quite ready. As cats are unquestionably the most authentic of creatures, offering no pretensions to anyone, not even to their owners, Cat’s judging gaze downward from high above the party-goers in Holly’s apartment symbolizes the judgmental gaze of authenticity downward at the shallowness of human activity below. Such, perhaps, is the judgmental perspective of every philosopher toward shallowness in others down below, from Plato’s Allegory of the Cave onward.

There are innumerable examples of falsity in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, from false relationships to a false engagement ring—found by Paul Varjak in a Cracker Jack box, no less, yet engraved with real engraving from the actual Tiffany’s, in a hyperreal blend of the artificial and the real that even French philosopher Jean Baudrillard would have to appreciate. From dime-store masks to Holly’s own alter ego—with shades of a personality disorder or neurosis—Breakfast at Tiffany’s perhaps makes Baudrillard’s sociological point that the artificial has so embedded itself into our day-to-day reality that it’s now impossible to tell the difference between the artificial and the real, between the simulation and the simulated, between the shallow and the substantive.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s is ostensibly a love story. After all, Holly Golightly and Paul Varjak have been settling for less-authentic relationships until they find real connection and authentic love together in each other. But lurking below this surface reading is a scathing criticism of the nihilism inherent to contemporary society with its emphasis on materialism over meaning, on glitz and glamour over substance. An historian with a Hegelian/Marxist bent might argue that every successful civilization, from Ancient Roman and Ancient Egyptian societies to Modern European and Contemporary American societies, must eventually reach an age of decadence in which sheer material wealth threatens to undermine the traditional values of the society—hence the shunning of materialism in favor of duty, minimalism, and military preparedness in ancient Spartan culture; the Spartans knew that material decadence was inevitably tied to the decline of a society.

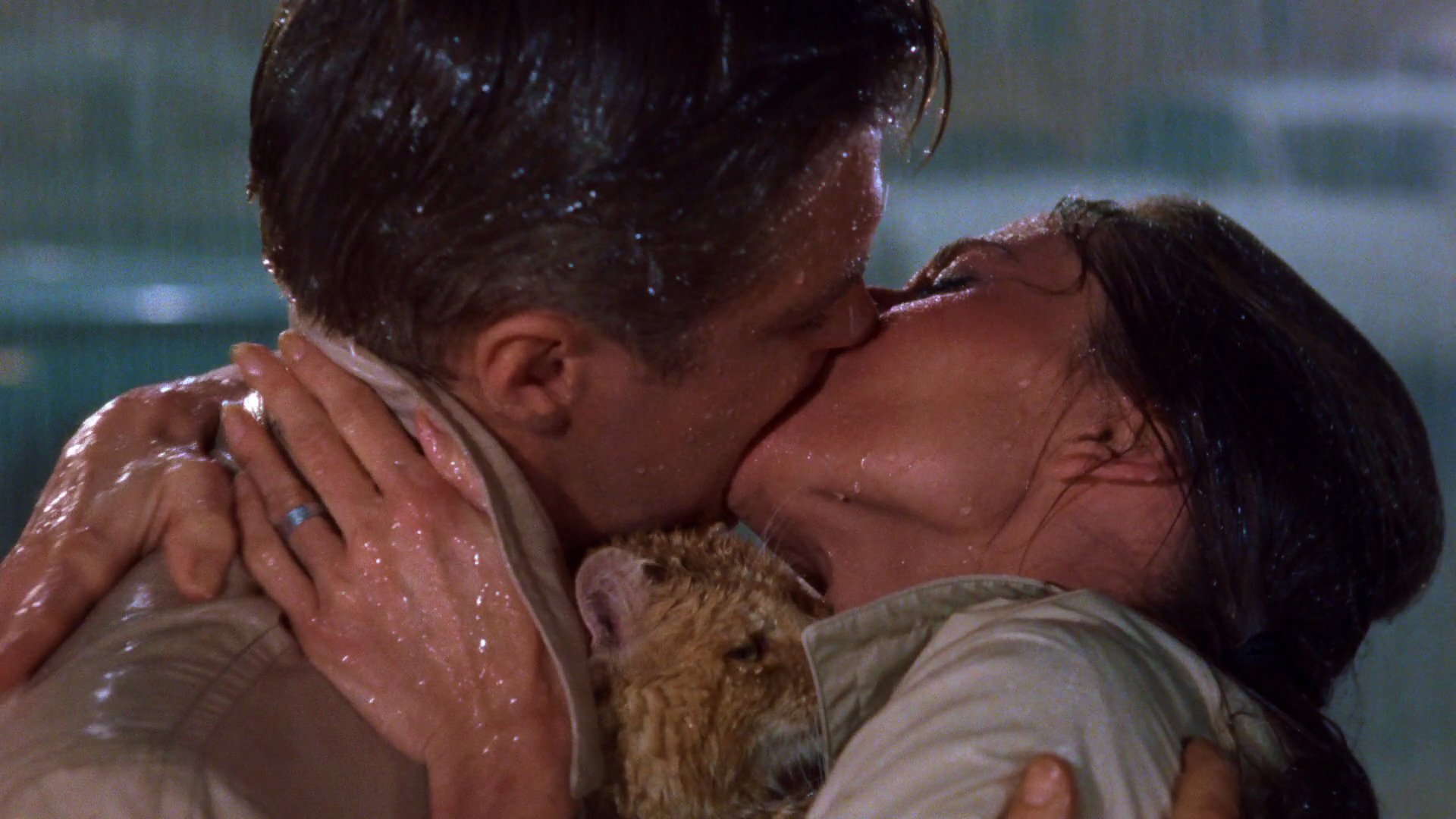

Yet, somehow, despite the nihilistic and materialistic forces at play in the snapshot of mid-20th-century culture depicted in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Holly Golightly and Paul Varjak are able to transcend the nihilism surrounding themselves to find a cocoon of real meaning and connection, a cocoon that shields them from the meaninglessness of the world around them, albeit one that fails to protect them and Cat from the rain in the film’s final scene. Breakfast at Tiffany’s doesn’t pretend to have the answer to the cultural problems of postwar American life with its affluence and shallowness. The film’s only answer seems to be that individuals are, despite the odds and the cultural factors at play, somehow able to carve out a bubble of authenticity in real connection with others.

As to whether it’s possible to reorient contemporary American culture, as a whole, toward a more authentic mode of being and away from decadence and trivialities, Breakfast at Tiffany’s remains frustratingly silent. We don’t get to see, for example, the redemption of the soul of 2E Failenson, of Holly’s brief fiancé José da Silva Pereira, or of the countless soulless party-goers present but not truly connected with in Holly’s nightlife. Were they, too, able to find real connection and escape the trappings of the decadent society into which they were thrown in some Heieggerian sense? Or were they simply creatures of their times with no more soulfulness and substance, to the very end, than the mere shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave? Obviously we don’t get the answer, but the film seems to imply the latter—that some of us are simply too embedded in the shallowness of the times to find redemption from the affluence, decadence, and meaninglessness of our present age.