Philosophy and Film: The Breakfast Club

The 1985 John Hughes film The Breakfast Club is an essential rite of passage for anyone who has grown up since the film was released, from 1985 right up to the present day. I recently rewatched the film and was struck by how well the film holds up, despite some glaringly outdated pop culture references and terminology.

As I rewatched The Breakfast Club, I was struck by how essential the central messages of the film are, not just for adolescents and teenagers but for viewers of any age, as I’ve come to see that the film is an allegory not just for friendship across peer groups in American public schools, but for the nature of friendship in general, one’s own personal and social identity, the various facets and tensions of our inner psychology, and more. In other words, The Breakfast Club is a far richer film with more so say than it is often given credit for, despite its status as an essential teen movie of the 1980s.

Each One of Us Is a Brain, an Athlete, a Basket Case, a Princess, and a Criminal

I don’t know how I missed the fundamental message of The Breakfast Club after so many viewings, but the core message in the film, as expressed by the essay that the character of Brian (Anthony Michael Hall) writes to Assistant Principle Vernon (Paul Gleason) after a day of Saturday School detention, spoke to me more on this recent viewing than it had before.

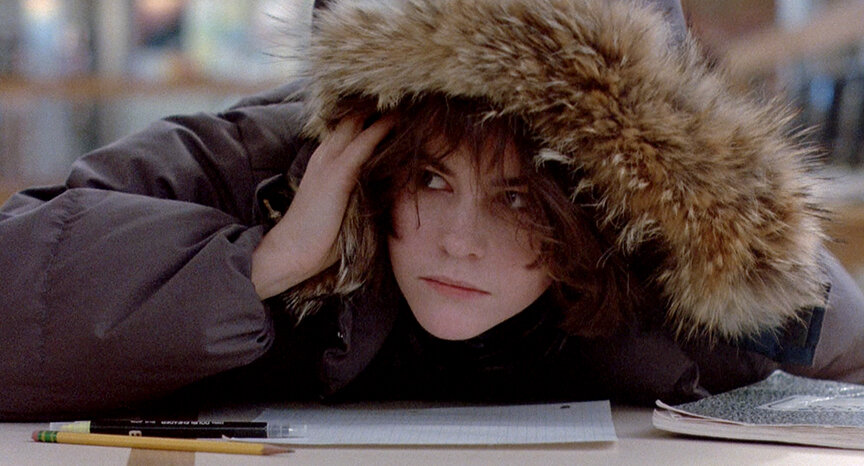

In the final audio lines from the film we hear the voice of Anthony Michael Hall reading the following words from his character’s essay, transitioning into the voices of each of the other student characters as the narration goes on:

Dear Mr. Vernon,

We accept the fact that we had to sacrifice a whole Saturday in detention for whatever it was we did wrong. But we think you're crazy to make us write an essay telling you who we think we are. You see us as you want to see us, in the simplest terms, in the most convenient definitions. But what we found out is that each one of us is a brain, and an athlete, and a basket case, a princess, and a criminal. Does that answer your question?

Sincerely Yours,

The Breakfast Club

The film’s final message is plain as day, and yet it is surprisingly easy to miss. These lines from the final moments of the film don’t apply merely to the five characters in the film. They apply to us—all of us!

Each one of us is a brain—we’re all good at something and love to geek out on the things we love, however serious or trivial.

Each one of us is an athlete, aiming for glory but finding one’s life influenced by the crowd and by peer pressure at the expense of thinking for ourselves.

Each one of us is a basket case, a beautiful and unique snowflake (reminiscent of the dandruff snowflakes from Ally Sheedy’s basket-case character) with our own social awkwardness and neuroses, the part of ourselves that just wants to run away and hide, and the part of ourself that feels ignored but longs just to be seen.

Each one of us is a princess, the center of our own lives and our own social circles, the linchpin of our social groups on Facebook and Twitter, with the feeling that we are special and even above the rest of the crowd.

And each one of us is a criminal inside, longing to be free of the social constraints, laws, and pressures to which other people seem to conform so easily—the part of ourselves that longs to run down the civilized halls of life and scream “Fuck you!” at the authority figures of the world, just as Judd Nelson’s character of John Bender does in the film.

Anyone who is even remotely introspective probably relates to each of these characters and sees their various character traits, for better or worse, in their own mind, life, and actions, however fully expressed or subtly repressed. Just as the characters of the film eventually learn to get along and become friends despite their obvious differences, we too (most of us anyway!), as the complex and multifaceted people we are, must learn to reconcile this inner tension between the various aspects of our personality that are constantly at war with one another, just as the character of Andrew Clark (Emilio Estevez) confronts John Bender (Judd Nelson) and west’s him forcibly to the floor. All of us struggle with something in ourselves that we have to wrestle with and subdue to become the best, most harmonious versions of ourselves.

Down in the Trenches Together

It occurred to me while watching the film this time that friendships formed between the characters in The Breakfast Club are an excellent example of a well-known phenomenon of wartime: the way in which people who go through a traumatic event together tend to become bonded, often forming lifelong friendships merely because of the shared traumatic experience, often even if neither party has much otherwise in common with the other.

The well-known phrase “down in the trenches” arose from this phenomenon in the world wars of the 20th century. When soldiers were literally downing the trenches together—a grueling, dirty experience in which everyone was afraid for his (or her) life at every moment—they couldn’t help but bond over the shared experience, and many a 20th-century lifetime friendship sprung up from the trenches and from the ravages of war.

In The Breakfast Club, the main characters are going through the teenage version of being down in the trenches together: a Saturday in detention, complete with boredom, a pointless (in their eyes) essay to write, classmates they despise but grow to love, and more. One can similarly imagine being stuck in a European trench with a group of fellow soldiers one initially despises but grows to depend on and even love, in some Platonic soldiery kind of way.

These unlikely friendships occur in real life, in war, in school, and in traumatic environments of all sorts, throwing doubt on the popular notion that your best friends are those with whom you have the most in common. My own experience with friendship, and the experience of the five teenage characters in The Breakfast Club, is that the best friendships often occur between those who actually have very little or even nothing in common but some shared experience, whether positive or negative.

We Are All Right and We Are All Wrong

In The Breakfast Club, judgements and prejudices abound. Each character seems to view the other four as beneath him- or herself. The judgments that each character makes about the others are both right and wrong, both true and false at the same time:

Brian (Anthony Michael Hall) is a brain, but he is more than a brain; he is empathetic, and he smokes pot with the rest of the crowd when the opportunity presents itself, even if he’s the only character at the end of the film not to be paired off romantically (there are an odd number of characters, after all). And, most memorably, he was in detention for bringing a flare gun to school which went off in his locker, having contemplated suicide because of the prospect of getting an F in his shop class.

Andrew (Emilio Estevez) is an athlete, a jock, caring far too much what others think of him and having never developed the ability to think for himself, letting his father’s influence and the influence of his fellow jocks (“sports,” as they are called in the film) steer his life instead of his own mind and own sense of self. Yet Andrew is also courageous, confronting John Bender physically and verbally while defending those Bender picks on in the first half of the film.

Claire (Molly Ringwald) is a princess, a prom queen, a spoiled rich kid (a “richie”), and queen bee of their high school. But she is also highly sensitive, as we all are, to what others think of her, and she is brutally honest about how she doesn’t think she’ll be able to maintain the new friendships she’s formed with her Breakfast Club cohort come Monday morning.

Allison (Ally Sheedy) is a basket case, a kleptomaniac, a potential runaway, and a socially awkward neurotic. And yet, she has dreams of traveling, of being seen and accepted, of looking as beautiful as Claire makes her look by the end of the film (with a very 1980s beauty makeover!), and she sees through the falsehood of the image and narrative of the other characters perhaps most easily of anyone in the group.

And John—called “Bender” in most of the film (Judd Nelson)—is a criminal who destroyed school property, rips books apart, lights things on fire, does and perhaps deals drugs, and more. But Bender (unlike Andrew!) is also skilled at shop class, sees through the artificial constructs and the bullshit of life, both his fellow students’ lives and the teachers’ lives (Vernon’s pathetic life in particular), and he is willing to let himself get in trouble for the sake of preventing his fellow Breakfast Club members from getting caught, particularly in the scene when all five of them are roaming the halls against the wishes of their relatively clueless detention taskmaster.

So each character in the film is both right and wrong about the others. Each of them is defective and screwed up in some way, and yet they are all able to transcend those aspects of themselves, individually and collectively, over the course of the film.

We too often make judgments about other people, and we are likewise often both right and wrong about other people, seeing them only through our own narrow, and likely equally as screwed up perceptual and judgmental lenses. And it’s just as important that we, too, here in real life, recognize the truth and falsity of the judgments we make of other people, objectively and rationally, and that we recognize the way in which our own perceptions and judgments are just as screwed up as anything we see in other people. This should breed a kind of humility and compassion in us in the same way that the various characters in The Breakfast Club become more compassionate with each other as the film progresses.

Sitting at the Cool-Kids Table

The endless popularity contest of high school isn’t over when you graduate. From elementary school through high school we strive to be cool enough to sit at the cool-kids table. Some, like Claire and Andrew in The Breakfast Club, succeed, while others, like Brian and Allison, fail to become cool enough to sit at the (literal or metaphorical) cool-kids table.

But the struggle to reach, belong at, and remain at the cool-kids table doesn’t end when school ends. The professional world, too, can be a hierarchical caste system in which some social groups are subservient to and even demeaned by others, no matter how flat our organizational hierarchies may be and how egalitarian we’d look to think we have become. Just like the new kid in school has to earn his or her way to a place at the cool-kids table, the new guy or gal in the office doesn't yet have any professional street cred (street credibility), at least not at at first at a new company or in a new organization. In the professional world, you are often only as cool as the last cool thing anyone saw you do, and only if that last cool thing didn’t take place more than a week ago. Institutions and their members have very short memories, so even if you were once successful or have a long history of success, the fight to remain at the cool-kids table or to find your place at new cool-kids table, as you progress in your career and as colleagues come and go, never ends.

So while The Breakfast Club is ostensibly about the perils and the promise of life in American high schools, it is really an allegory for all of life, the way in which we constantly begin as outsiders and have to earn our way into the inside circle in any social environment, and the way in which we have to navigate the perilous waters of competing, overlapping, and conflicting social groups while jockeying for position and power.

The State of Nature and Social Contracts in The Breakfast Club

Philosophically, The Breakfast Club is a plausible example of the State of Nature as described by Thomas Hobbes, a war of everyone against everyone in which life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Hobbes, Leviathan).

(Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes)

According to Hobbes, mankind’s natural state is one of fear, endlessly struggling to preserve one’s life, sustenance, and belongings from the ravages of nature and the thievery and barbarism of others. To eliminate the fear inherent to our natural state, according to Hobbes, we band together and form what is known as a “Social Contract,” an agreement not to kill each other, steal each other’s resources, and so on. We form primitive societies with their own laws, morality, and social conventions, all for the sake of safety and security in a world that is fundamentally harsh. Outside the State of Nature, for Hobbes, there is no morality, no right and wrong, and one is back in a war of everyone against everyone.

In The Breakfast Club, each of the main characters is safe in his or her social clique. Brian is safe with his nerdy friends in his academic clubs. Andrew is safe with the fellow sports in the locker room. Claire is safe with the richies in the hallway and while shopping with her friends at the mall. Bender is safe with his stoner friends. And even Assistant Principle Vernon is safe with his fellow faculty members; he’s known as a “swell guy” as he puts it in the film. Ally Sheedy’s character, Allison, is the only character who doesn’t appear to have a social group; hence is safe with no one and feels utterly and completely alone, afraid of everyone and everything.

When the five protagonists of The Breakfast Club, from five different primitive societies and social contracts are plucked from the safety of their cliques and placed into detention with one another, they are thrown back into the State of Nature of Thomas Hobbes, a war of everyone against everyone in which there is no refuge. The threat, of course, in the State of Nature depicted in the school library detention zone in The Breakfast Club, isn’t literally of life and limb (although Bender does threaten Andrew with a knife at on point in the film, threatening to kill him with oh-so-much hot air); the threat in the film is a loss of one’s social status in the face of competing social groups vying for supremacy, much in the way that Thomas Hobbes suggests that societies and governments are formed not merely to deal with internal threats but threats from external invaders and other societies as well. John Bender is a threat to all of Claire’s rich-kid values, just as Brian is a threat to, and a mirror for, the superficiality of Andrew and his fellow jocks. And Allison’s loner and isolationist ways are a threat to the artificiality of each of the other social cliques depicted in the film.

Although each character in The Breakfast Club makes an impressive effort to hold on to his or her social identity in the face of the threat to that identity presented by the other characters in the film, eventually the walls—the emotional walls and the walls of identity in the film, and the literal walls in Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan, come down. The Social Contract is broken. None of the characters is required any longer to hate any of the other characters, because they have rejected the social contracts of their groups that they once relied on for safety and for their own identity, essentially forming a new Social Contract between the five of them in the process, just as citizens have overthrown oppressive governments and regimes in every great revolution in the history of civilization itself.

Which Social Groups Still Exist Today?

The social groups depicted, or alluded to, in The Breakfast Club are a product of the 1980s. Some of them, like jocks and brains, have likely always existed. I imagine that there were jocks and brains even in Ancient Rome, Ancient Greece, Ancient Egypt, and even in the ancient Mayan and Native American civilizations of the Western world. And as long as there have been material possessions there have always been “richies,” despite the inherent tension between individual and communal property ownership from society to society in the history of the world.

Some of the social cliques alluded to in The Breakfast Club are more a product of its time than a universal truth. The “stoner” identity of John Bender is arguably a product of late-20th-century drug culture, although in reality the use of substances to alter human consciousness has a history just as long as the history of material possession. Whether it makes sense to say that there were Ancient Roman, Ancient Greek, Ancient Egyptian, Mayan, or early Native American stoners is not fully clear. Did the presence of consciousness-altering substances, or even their frequent or habitual use, automatically mean, perhaps by definition, that there were stoners in the ancient world? Or is the modern conception of Bender as a stoner a product of radically contingent social and cultural factors highly specific to the late 20th century?

I personally find Judd Nelson’s depiction of Bender as a stoner, however insightful it may have been in the 1980s and even into the 1990s, a bit anachronistic at this point, even though drug use remains a problem. Something about the social nature of drug use has changed between the latter decades of the 20th century and the early decades of our 21st century today, although I am hard-pressed to be able to say what exactly the difference is. Perhaps we are more casual about drug use today, less inlined to criminalize it in ways referred to in The Breakfast Club. Perhaps drug users are even more social outcasts than they were in the 1980s and 1990s because of substance abuse awareness programs like D.A.R.E. America. Perhaps there is social pressure to act less rebellious than Bender acts in The Breakfast Club. Whatever the change, I find the stoner archetype of Bender in the film not to ring as true today as it once did.

I also find the incessant materialism and superficiality of Claire’s character to be a bit outdated at this point as well. One must remember that the 1980s were commonly seen as a decade of greed and affluence, as seen throughout 1980s popular culture, everything from Gordon Gekko’s statement that “Greed is good” in the 1987 film Wall Street to Madonna’s statement in her song “Material Girl” (from her album Like a Virgin) that she’s a “material girl living in a material world.” Although there are still rich people today, one could argue that the social barriers between rich and poor, at least in America’s shrinking middle class, have largely broken down, even as the rich get richer but smaller in number and as the poor get poorer and larger in number.

I think, however, that Ally Sheedy’s portrayal of the Allison character is perhaps the true universal constant in the film. There have always been loners, social outcasts, and runaways in the history of the world, whether by force or by choice, those who turn their backs on the civilized world for a more sane-making solitary existence, from the ancient Cynics to the Medieval monks, from the Henry David Thoreaus and Friedrich Nietzsches of the world to the kids who sit alone in the back of classrooms and cafeterias across America and around the world. And those loners have the same inner strength and razor-sharp perceptiveness that Allison displays in the film when talking to Andrew in the hallway, calling him out on the line of bullshit he feeds her about the reason he’s in detention in the first place. It’s not clear at all, however, which social groups and cliques from the 1980s are historically contingent and outdated to us today and which are truly universal, likely to exist in any culture alive today and in any that has ever existed in the whole history of humanity.

Conclusion

If you have been watching The Breakfast Club, perhaps nostalgically, only as a narrowly-focused 1980s teen movie, you have really been missing the point and the key messages of The Breakfast Club and what it has to say about the human condition universally in any context, from the classroom, cafeteria, and school library to the cubicles and corridors of today’s dysfunctional office and workplace cultures.

Competing social groups exist in every context, from elementary school to the retirement home, and we are all vying for position while avoiding the fear and insecurity of the State of Nature without a social group. We all war for each other for popular opinion and our rightful place at the cool-kids table, either literally in school or metaphorically in the professional world and in our overlapping and often superficial social circles.

The social cliques in which we find refuge often fail to bring us the security and fulfillment we long for, and people sometimes rightly turn their backs on those social groups and their necessary peer pressures in search of a new social group that provides what previous ones could not, even if it’s in a band of ragtag misfits and outcasts, whether in detention or in the trenches of war—or of life.